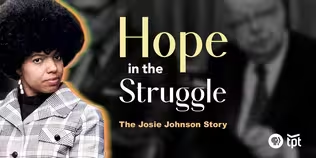

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story

Special | 56m 39sVideo has Closed Captions

A reflection on the life of freedom fighter and civic leader Dr. Josie Johnson.

A reflection on the life of freedom fighter and civic leader Dr. Josie Johnson, who fought for fair housing, education, and civil rights. Hear in her own words how her experiences turned her to activism, what action looks like, and how the next generation is taking up the mantle. The struggle for justice and equality continues, but there is hope in the struggle.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story is a local public television program presented by TPT

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story

Special | 56m 39sVideo has Closed Captions

A reflection on the life of freedom fighter and civic leader Dr. Josie Johnson, who fought for fair housing, education, and civil rights. Hear in her own words how her experiences turned her to activism, what action looks like, and how the next generation is taking up the mantle. The struggle for justice and equality continues, but there is hope in the struggle.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

- [Josie Johnson] There are some men on the board who still consider us little girls and ladies.

(dramatic music) - [Eric] The legislature elected the first person of color, Josie Johnson, to the University of Minnesota Board of Regents.

- [Josie Johnson] I was invited to the League of Women Voters, the NAACP, the Urban League.

- [Josie Duffy] She was at the March on Washington.

- [John] The whole spectrum of Josie's commitments crossed the lines of color, and class, and gender.

- [Sharon] She played a lead role in helping to dismantle those rules and regulations.

(crowd yelling) - Young Black millennials, for years, have been asking me why.

Why do you stay in the struggle, and then why do you have hope?

- Having hope makes it possible to continue not just for your life, but for the lives of everyone who came before you and everyone who will come after.

- I don't think it's my right to not have hope because she's, 'cause she did it, and things were worse.

So even the days that things feel not great, I have to remember, like, what she did at 15, what she did at 20, what she did at 30 and 40, and, you know, what she did her whole life, really.

- And I think about all of the stuff that she's seen, what it must take to keep a spirit about you that's positive and optimistic.

- Sometimes it works in some ways and sometimes it doesn't, but it's incumbent upon you to try again and find another way.

(soft music) - Too few of us, me, my ancestors, see the changes that are supposed to have happened to really feel something changes.

- [Josie Duffy] You know, growing up in Texas in the 1930s is not where you're seeing the best our humanity has to offer.

- [Josie Johnson] The issues facing Black people were deep in the fabric of American policy, life, understanding.

- What she saw, how hard it was to convince people that, hey, we deserve to vote, we deserve to live in a house, we deserve to have a job, we deserve to have equal rights.

- My parents raised me in Houston.

When my father graduated from college, he wanted to go to law school.

There were no graduate programs by African Americans in the south.

My father couldn't afford to go any other place for graduate school.

So he did what many Black men of that generation did, and that was to work for the railroad company as a dining car waiter.

(gentle music) He organized the dining car waiters during the same time that A. Philip Randolph was organizing sleeping car waiters.

He was involved in organizing the Urban League in Houston.

He was... (Josie laughing) He was involved in anything that dealt with civic engagement and an opportunity for justice and equality.

So I grew up in an environment of my father organizing and being engaged, and my brothers and I would sit and listen to him as he talked with the process of organizing.

Texas had introduced the poll tax in 1902.

The poll tax was a receipt that you received if you were able to pay to get a receipt that said you were a citizen, you could afford to pay the taxes that you were charged to vote.

We went door to door, and I accompanied my father.

I was always (laughs) with him.

The belief that if you had enough signatures, that would impress the government, and they would then do away with that method of denial.

But it didn't matter.

The right to vote nationally was, what?

'66?

Texas decided that it would not honor that.

(gentle music) (soft music) W.E.B.

Du Bois was my hero because he was very forward thinking and so much dealing with African American history.

Everything I thought about in my formative years, W.E.B.

had already thought about it, written about it.

He loved our people.

He understood what had happened and why, what it meant to be a poverty stricken people, and how society saw us.

My respect for him allowed me to understand from whence he came, but how he could write about, talk about us as a people.

He was a Fisk University person, which is my alma mater, so I was excited to be near the place where my hero worked.

(soft music) - At Fisk University, where she underwent some of the same questions about what was her focus in life, her direction in life, and the role that the staff and faculty and the students at Fisk had in helping her clarify those issues in terms of her own educational process.

(soft music) - Think at 16, I was in college that had a history of Black engagement, Black historians, civil rights protestors, workers who came and told us about the struggle.

We had people who were working for and about us.

We had all kinds of things going on at Fisk.

So I saw all of this, and there was always the hope that we would get there.

We got married almost immediately out of college.

My husband been given a scholarship to go to MIT and was drafted into the service.

He went to the military base that did the work on nuclear energy in Texas.

Our second daughter was born in Texas, and when she was six weeks old and my eldest deceased daughter was two, Charles accepted a position at Honeywell.

That's what brought us here.

That was 1956.

I felt we were very fortunate to meet the people we met.

A wonderful community of Black activists and others.

I was invited to the League of Women Voters, the NAACP, the Urban League.

So I had an opportunity almost immediately to learn about my city and to be engaged.

- I know that a lot of change has happened, but I'm sure she's seen a lot of things repeat itself, and so I know that it takes a lot of inner peace, and positivity, and hope, and optimism to kind of push through the idea that things maybe are moving slow or possibly won't change, you know.

I am still working on that part myself because without kind of that hope in the struggle, it's hard to continue with an idea that you're able to make a difference.

(gentle music) (hammer thudding) - [Josie] 1956, we were very much involved in issues dealing with housing discrimination.

Exactly.

Many people don't know housing was an issue of discrimination, and I was the chief lobbyist for the Fair Housing Legislation in '62 and Katie was one of- - Well, I was thinking about where this country is going and where the city of St. Paul is going... - And to those who own property have a right to sell and a right to rent to whom we please, and the white people, the white race, had better wake up and see the handwriting on the wall before it is too late.

I don't feel... - In housing, we did some testing of what goes on in real estate, banks, covenants, where communities could say who could move in and who could not, or have you sign a paper that said you would not sell or rent to a Black person.

So we tested many of those methods, and they were pretty obvious when you think about it now.

I would go in to rent a piece of property, and I would be told that it's not available.

We'd send you in and it would become suddenly available.

So there were all of those formal and informal methods of denial.

(soft music) There had been for years, late '50s, organizations within our city.

They were very eager to create an environment of open access to housing.

Well, it didn't work.

There was the sense that what we needed to do was to really create a lobbying effort at the legislature in the '61 session.

So I was encouraged to be the chief lobbyist for that, and I invited my friend, Katie McWatt.

- Some parts of the housing market, the effect of the law is fabulous in a sense.

- We worked throughout that legislative session to support a bill that Senator Don Fraser and Representative Bob Latz had introduced to their bodies.

In my lobbying, I felt we were losing the vote, and so I went to Governor Elmer Andersen.

He was a very open, fair, liberal Republican, one I knew and had a lot of respect for, and I said, "Governor, the housing bill is gonna be defeated in the judiciary committee, and I'm very worried about it."

So the governor went to his desk and got stationary and wrote a note to each member of the judiciary committee urging them to allow the bill to get out of the committee, that it was only fair and just in his judgment, and allow it then to be treated in the full senate, and the bill passed by one vote.

So it then got to the full senate, where it passed, but, again, narrowly.

- Criminal protection as well as the belief that discrimination practiced against any individual is a threat to all.

Now, therefore, I am... - Minnesota was one of the first states to pass a fair housing.

We didn't pass a National Fair Housing bill until 1967.

You know, I've been very troubled because there was still so much discrimination in housing, and how do you implement a law that says that's not supposed to happen?

- She played a lead role in helping to dismantle those rules and regulations to make sure that we had opportunities to fair housing.

When Vice President Mondale was in the senate, Josie Johnson was working right alongside of him to help make those things happen.

She was the voice for the African American community in the Twin Cities and as well across the nation.

- Before it was sort of trendy to talk about allyship, my grandmother was finding out how to make the biggest impact.

And she wasn't necessarily saying it could only be us, she was, in fact, saying, it's all of our responsibility and it's yours too.

Rising tide lifts all boats, right?

So the responsibility that we have to build a better society for everyone.

- My five-year-old, we've kind of talked to him a little bit about, you should know her, you should talk to her, you should ask her questions.

But what's interesting is that some of the things she's fought against, he can't even imagine being problems.

He doesn't understand being in a different classroom than his white classmates.

He doesn't understand not being able to vote.

The things that she's helped make happen are so familiar to him.

The fact that he doesn't totally understand is a testament to her work.

He was very interested when, on Martin Luther King Day when we said Gigi was at the March on Washington.

(soft music) - The March on Washington had been discussed in the '40s by A. Philip Randolph who felt that we needed to protest.

There needed to be an expression of concern about denial and the lack of national progress in the issues of housing, employment, education.

But nothing really happened, so the threat of the march was introduced again, and this time there was the effort on the part of John F. Kennedy to encourage him not to do it.

But it was such a critical need to demonstrate that there was national interest in justice, fairness, and opportunity.

(soft music) In 1963, we were lucky to have Bayard Rustin work as a organizer, and he was able, in a brief time, to bring the whole nation together.

There were rules and regulations that we had to follow.

We had to sign a pledge that we would not react to abuse or mistreatment that we might experience while we were there because skinheads and others had vowed that they would not allow the march to take place.

And so we had to sign this pledge in order to honor the peaceful march.

For one of our members, Dr. Thomas Johnson, he said, "I can't sign that.

I can't pledge that if someone attacked me, I wouldn't retaliate."

So he didn't go.

We were so prepared for the trip.

We left Minneapolis around 3 or 4 AM and landed in D.C. We were met there, taken to a church.

Our congressional delegation, Hubert and Don Fraser and Art Naftalin, who was mayor then, went with us.

There was a sense of protection.

In fact, I was so worried.

At the beginning, I didn't see anyone.

The streets were quiet, there were no people around, and I said, "Oh my goodness, this has failed."

So we were in the lower level of the church, and by the time we were ready to leave, the excitement, the people coming from every direction to the reflection pool, and it was a hot summer August day, our group felt really united.

We all had this great respect for Dr. King and of course the program itself.

- Freedom, freedom, freedom to all!

(crowd yelling) ♪ We shall overcome someday - And we were all instructed that we are to leave immediately after the program ended so that there wouldn't be the fear of being attacked.

- This march will go down as the greatest demonstrations for freedom and human dignity ever held in the United States.

- The biracial, mixed religious groups reflected the diversity, the respect, the attitude that we had about our struggle and what we were fighting for.

It was there.

Displayed.

(triumphant music) - I think my grandma took on a lot because there weren't always other people to take it on.

I mean, you know, my mom and my aunts grew up in a largely white community.

My grandmother obviously was very often the only Black person in the room.

Very often the only woman in the room.

She didn't really always have the luxury of choice when it came to, like, how are we going to do this?

There is an ultimate goal and there is a immediate goal, and sometimes the ultimate goal takes total restructuring of everything.

But the immediate goal means you have to go to the city council, you have to go to the state legislature, you have to go to Congress.

The right thing doesn't just happen, right?

You actually have to put in some elbow grease into making it happen.

- My fear was more in '64 when I had to go to Mississippi.

(tense music) In 1964, Dorothy Height, who was head of the National Council of Negro Women, Dorothy and some of her Jewish friends worked on involving women in the struggle.

They organized what they called Wednesdays in Mississippi, and they invited groups of women to go down to Jackson, Mississippi.

So it was a organization of women, for women, about women, but that it was to be a secret.

We couldn't tell anyone.

It was very dangerous.

People killed, and homes bombed, and churches bombed, and children thrown in jail.

My husband and I had quite a conversation about whether I should go.

I had three daughters, six, eight, and 10, and the question was what if I didn't come back?

- The enormous risk and stress that is to leave your kids, your three very young kids, and risk your life to be a relatively small part in a much bigger thing.

In other words, it could have not worked.

- But after a little bit of conversation, my husband being very respectful of all that I'd been engaged in, we finally agreed that, yes, I should go.

(tense music) You'd heard so much about the Klan and other mistreatment of us as a people.

So when we arrived at the Jackson Airport, our host family had not arrived yet to get us.

I envisioned the Klan picking us up, (Josie Johnson chuckling) taking us away.

Our host family came and took us to a very large Black Baptist church that was having one of its training sessions for instruction on approaching people, organizing people, and work towards signing people up to vote.

There were Black men patrolling the church with shotguns to protect those of us in the building.

(gentle music) When we left the church, we then went to a restaurant in the Black community, and we were told to be very careful.

- I was on the board of the National Council of Jewish Women.

One of the things they did right away was pull the drapes so that they would not see strange people, white people in their house.

Another thing we were told, not to, if I was walking with my companion, not to talk out loud because they would detect a northern accent.

We were told that in case a police car was following us- - That's right.

- highway patrol were not our friends.

- That's right.

That's right.

- Yeah.

- Well, you know, we knew that the FBI wasn't our friend either, so.

- I know.

- But we were... And if you remember the three young men, civil rights workers had not been found yet.

(gentle music) Yeah.

Yeah!

- Beautiful right there.

- And the swampy areas on the side, and I can remember saying, I wonder where those young men are.

Maybe they're over in... - One of those swamps.

- One of those swamps.

We then went about our work.

Meeting with families, going to court, listening to our children being sent to jail and parents crying, and reports of abuse.

As a Catholic, I met with Catholic priests, we met with other denominations.

We were all told how fearful ministers were to talk about voting rights in their congregations because they didn't know who was listening and who would report what they were doing.

After Mississippi closed all of its schools, there was an effort to continue to educate Black children.

So churches became academies for our children and freedom schools were created.

So a lot of our young white students and Black students organized these freedom schools.

Later that evening, we learned that the freedom school was bombed, and for many years, I felt guilty about that because I thought if we hadn't gone to that freedom school and maybe if the Klan and other persons who were still trying to deny us an education opportunity had not known we were there, they might not have done it.

Our white members had to be very careful in visiting their white co-interested people in Jackson because, in many cases, these were wives of men who were very involved in the denial of voting rights and civil rights activities.

We were told that we had to be rather low key about all of it.

So when we came back, we were not really encouraged to do much talk about it except our report, about what we saw, what we heard, what we knew was going on there.

That report went to the attorney general, and it went to the committee that was writing the bill to support civil rights.

(soft music) Maxine, my friend, when we came back, received ugly letters from people wondering why she went.

- When we did get back, there was publicity about us in the paper- - There was, yeah.

- at which point, I got several very mean anti-Semitic calls and some anonymous letters.

My husband thought they were a bunch of kooks, but I thought it was pretty scary.

- Yeah.

She experienced... And that's Minnesota.

What I think we have to understand in Minnesota is that we are not immune from all of that.

(soft music) As we grew in number, our people in number and our kids in the schools, the real issue of discrimination becomes very clear.

And Minnesota...

When your whole philosophy is based on a very limited amount of experience and exposure, you then make policy that you don't realize denies others and still benefits from what you know.

- I didn't, growing up, recognize how pioneering her activism and engagement was, being this woman who was sort of fearless and decided to go to the front lines, and what a sacrifice that is.

When you're a kid, the things that your grandparents or even your parents do are sort of outside of your bubble, right?

You don't really have a relationship with who they are in the world, it's just who they are to you.

- I really learned from my grandmother the importance of fighting for people that the government was not looking out for.

It's important to fight for everybody.

You have to push people in power to do better and to do the right thing, and that it's not always self-evident and that the right thing doesn't just happen.

(gentle music) - My mother worried about my brothers being away from the home after dark.

She could not rest until my brothers were home.

So it's not a new thing.

Police-community relations have been an issue, and for some reason, even back in the Minneapolis civil rights days, one of the things that was recommended was that we create programs that would assist our enforcement officers and personnel to understand their clients, the people they serve.

The north side community had the most activity.

It was also a very strongly Jewish community.

What had one time been a highly trust community and a good relationship began to lose some of that togetherness.

And so the community on the north side, I think, saw more changes socially than the south side.

Some of our children feeling oppressed and abused by the police.

There was this moment, it happened soon after the Aquatennial... - That the instigators of these incidents are lawless individuals who are seeking to inflame people of the community by creating situations of trouble for everyone in the city.

- Children reported having been abused by police and even reported that one of the little children, who ran into the street by mistake, was mistreated.

(somber music) Kids couldn't get on the bus to ride back to north Minneapolis.

There was just a lot of ugly things going on.

Walking back from downtown and their anger building up about what had happened to this child and not being able to get on the bus, they acted out.

(somber music) (alarm blaring) - Concerned about here today to get some kind of guarantees that there will be some things being done immediately.

- Mayor Naftalin was elected in '61.

You know, he was the first Jewish mayor for the city of Minneapolis.

Art Naftalin was very interested in civil rights and justice.

I worked for the Urban League.

I had an opportunity to work with the mayor on some of the issues.

He really wanted to know more about our community and our needs.

I served as a link between our African American community and city hall.

(gentle music) - In some ways, she's this quintessential grandmother, in other ways, she was always much busier than most grandmothers.

We would go visit, and we'd be going to meetings and projects.

And she was kind, and she was really kind to the people that she encountered, and she always used to tell us she was making us grandma noodle soup, and it was like this big deal.

We were so excited about getting grandma noodle soup.

And many years later, we discovered it was Top Ramen.

So, you know, she was like not the kind of baking all the time, cooking all the time grandmother.

She took great care of us, but she was really invested in community, and that's where she spent most of her time and where she took us when we went to go visit was to meet her friends, and to see her people, and to kind of be outside, not inside making homemade soups.

- Growing up, my grandmother was my biggest cheerleader.

And then as I got older and I kind of opened my worldview a little more, it was easier for me to place her as somebody who was something specific to me, but also so many things to other people.

- But in general, I think my grandmother, I think she believes that they're, that people are changeable and that, fundamentally, most people are good.

Look, that's the only option.

What she really, really always wanted was a better life for Black people in Minneapolis.

And if that meant going to the Republican governor, if that meant working across the aisle, like, she wasn't gonna let that get in the way of making a better life for the next generation.

(gentle music) - There was a national move in the mid '60s for universities and colleges to add African-American history to its curriculum.

Most of them didn't have it.

They had American history and they'd have a chapter on us in it.

And so our students began, across the nation, in very prestigious institutions, demanding that African-American studies be added as a department.

And our students here at the University of Minnesota had that same expression of need.

They had talked to administrators, they had tried to demonstrate the need for African-American studies, and they weren't being heard.

So they took over the building.

They decided they weren't gonna leave until they had an opportunity to visit with those that needed to hear their position.

- And that's the truth: you're being inconvenient.

We believe that you cannot wait a hundred years to fill the bellies of hungry people.

- I first encountered Josie in connection with the student group that I was a member of, the Afro-American Action Committee.

And our reaction to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, and that would lead ultimately in January of the following year to the Morrill Hall takeover that we undertook in honor of and in the spirit that Dr. King was so closely associated with.

- You, what are you gonna do?

- They're holding the building which we pay $135 a quarter to be able to use.

They don't pay anything.

- Josie was one of the community leaders and elders who came to our support.

Was physically on the scene in Morrill Hall during those crucial days and hours when we were trying to negotiate with the administration.

- I'm suggesting that if you were committed to do something about the problem, this kind of thing would not have to take place.

- There was some of us who then protected those students, you know, made sure they had food and police weren't harassing them.

(gentle music) Through their effort and the effort of a lot of white kids supported our students, and they all stood arm to arm and leg to leg, (gentle music) the department was created.

I was one of the first faculty.

I taught two classes: Black families in white America and Black people and the welfare system.

- She was a very strong advocate for more Black faculty at the University of Minnesota.

And when there was faculty, new faculty on the campus, Josie made sure that those people were introduced to the community so that the community could leverage the knowledge, the information, and the expertise that those individuals had.

She was always making those connections.

Josie Johnson was a champion for that work.

(gentle music) - When the opportunity for a candidate for the Board of Regents, my friends put my name forward, and I really did not know that I had to go before committees for both the House and the Senate to be questioned and to prove that I qualified.

The big vote came, I wasn't even there.

My eldest, my deceased daughter was in a play so my husband and I went, and when we got home, I received the call from the press telling me I had been elected.

- The constitution of the State of Minnesota that you will faithfully and impartially discharge... - I knew, instead of being token, I felt that I was, I had this opportunity to bring to the table another perspective and point of view.

So if others saw me as a token, I didn't see myself that way.

I saw that opportunity to make a difference, to have an impact, to have the voice of my people heard.

- If kids comes to school with all the sort of deprivations of poverty and broken families and all that, I'm just wondering what on earth is culturally sensitive education gonna do for that student?

- We have been looking at records that have proven that the system is not working well for children of color, and that's the reason the subtitle here is called "A Wake Up Call" to remind us that education really doesn't work uniformly for all children.

Knowing that, we also know that our children... (gentle music) We had the highest rate of nuclear families as late as 1980.

After that period, things began to really break down.

The Black education level was equivalent to white education level, and yet Black people were not hired.

We were denied housing opportunities and promotions of all kind.

So you can't have generations of attitude, policy, philosophy about who we are and not have that impact the social structure around us.

What happens to a people when you are denied on a constant basis of what you think is your right?

And here we are in a state that is supposed to be one of the most liberal in the nation.

It was very troubling to have our people not being able to get the kind of service that they deserved and then having to just do the best you can do.

- [Interviewer] You mentioned your oldest daughter's name, Patrice, twice, a couple of times in the last few minutes, and I wonder now whether we can talk about her death?

- It's not easy, so I can't just yet.

- [Interviewer] Okay.

It's the process of grieving that's ongoing then?

(somber music) - Monday, August 7th, 1989 is a day I will never forget.

- It was the day our family was changed forever and I lost my firstborn child.

- I had been in a meeting with a colleague... - I left the conference room at the end of the meeting and returned to my office.

When I checked my phone messages... - There was one from General Colin Powell.

I couldn't imagine why General Powell would be calling me at this time of day only to hear the most devastating news anyone could ever imagine receiving.

- He had called to tell me that a plane carrying Patrice and Congressman Mickey Leland had gone missing.

- Patrice was traveling with him in a delegation of 15 on a government mission to bring relief to Sudanese refugees.

- Chuck, Noreen, Josie and I tried to keep up hope and relied heavily on our spiritual faith.

We were blessed with the support and prayers of our family, friends, and all who knew Patrice.

- The rest of the day and, in fact, the next period of my life was confusing and sad.

- My life became an unbelievable experience during those horrible seven days of waiting.

As much as I tried to maintain a sense of normalcy, I could not.

I tried to work but couldn't focus.

I began to feel that I had died.

- I started putting my personal things in neat stacks and keeping them in places where they could be easily found if I died.

- The plane had vanished while attempting to fly through heavy rain, wind, and thunderstorms to its destination of Addis Ababa.

(somber music) - Sorry.

- I saw Patrice in everything I did.

- I saw her as a young girl playing on the swings in her elementary school yard at the University of Minnesota.

- As a teenager, a college student, and as a grown woman.

And I dreamed of her every night.

- In my dreams, she talked with me and tried to tell me not to worry.

- In one vivid dream, I saw her dressed in white as though she were an angel, and she said... - "Mom, I am okay.

Don't worry."

- That experience will stay in my memory forever.

My poor Grammy.

- [Interviewer] She was a super achiever in a family of achievers as I understand.

- Yes, she was.

She was very special.

(somber music) - You don't realize how strongly something is affecting you until you kind of get to a place and you look at it and you're like, "Wow, I'm doing exactly what my grandma instilled in me, which is like building community."

First and foremost, my grandma's library influenced me heavily.

When people ask about the work that I have in here and they're like, "Okay, well what are you trying to sell and what are you trying to tell 'em?"

I'm like, "I don't control what liberation looks like to anybody.

I just want to be able to provide literature to folks to find their own way."

And I think that's heavily influenced by my grandma, which is why she's the biggest piece of work on the wall.

I want her to see herself in this space and kind of what she's taught us kind of carrying on.

- I never felt like there was only one way to be active.

The role that I have on the work that I do is the form of activism that I engage in right now.

The nonprofit that I work for supports women in entering and reentering the workforce - Called the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children.

A place known as...

I learned from my grandmother very strongly that it's important to fight for everybody.

And I have really internalized that in my own work and will be trying for the rest of my life to kind of emulate her work.

(soft music) - Having grown up in a family and a community of people who were always working, knew that we would be struggling, but I think that at some point, we wouldn't have to struggle for some of the things we are still struggling for.

You know, I admire the effort that our young people are making.

When you don't see the changes that have been promised, what you do then is invent, work at changes that you think will matter.

And so our Young Black Lives Matter, on the heels of all that was going on with our police and Black people, changes have not happened, so let's try something else.

(crowd yelling) (soft music) Media paints a picture of who they are.

The Justice Department paints a picture of who they are.

That's the image they know.

And we have got to do more as elders and others to help our children learn from which they've come.

They've come from grand history of Black men and women.

(soft music) See, I think they have to know that learning is a part of who they are and that education is our emancipation.

That's what our ancestors said.

So you go to school as a serious student.

- [Teacher] Yes, the super script tells you how many... - [Josie] Our job as adults is to make it possible for you to be that student and the environment that says, "If you do all of this, you will have an opportunity beyond that to go to college, to get a job, to be successful."

(kids yelling) (people chattering) - We got you.

- This is where our preschool and toddler families come through.

As you can see, we've got our beautiful painting of Mama Josie.

The children learn about Mama Josie starting in preschool.

And so they understand her legacy, they learn about her journey.

So this is one of my favorite corners of the school.

This is Black Wall Street, also known as Entrepreneur Corner.

- We met Dr. Josie together, and right away, I could feel the energy.

It also reminded me of my wife.

It reminded me of her.

- Good morning, baby.

- I had never met her in person since she was a little girl.

She's been working for our people and has a big heart for education.

It just clicked right there.

I was like, you know, my wife is walk, actually walking in the footsteps of Dr. Josie, and so that's the name that belongs on the school.

- I wanna thank you all for being here today to celebrate a remarkable visionary leader, Dr. Josie Robinson Johnson.

- It was important to us for the children to see Mama Josie celebrated.

She means so much to the school and to the children here, and a great opportunity for the children to actually meet the person that they've been learning about and who they have been walking in the footsteps of.

- Josie's work not only exemplifies her burning passion as an educator, but it also represents a guiding light of inspiration for all of us.

- A folding turn in her concentric, overlapping circles of life and selfless service.

- Thank you, thank you.

- It means a lot, I think, to all of us to have, for her to see the impact she's had on people.

(soft music) (people chattering) - Lady of Civil Rights for Minnesota opened many doors, paved many ways for women like me, little girls like me, but also just Black people in general.

Something... - And because of you and the shoulders that we're sitting on... - After over a decade of being in Dr. Josie's orbit, I'm still just as inspired, just as awestruck, just as motivated.

- You have been so helpful to me especially... - That you see my blackness... - It says Josie is fearless.

- Yeah.

Embodiment of all the things that I was looking for and someone to look up to that was from the same state as me, that lived here and did such beautiful work.

- To give you what is our highest award to recognize the decades of your legacy and the future that you've insured for us.

So thank you for everything that you do.

(people clapping) (soft music) - To be engaged in making us better each day than we are at the beginning of that day...

Sometimes what is required of us oldsters is to remind our young people whether we've made any progress so that they don't get discouraged.

Where were we, where are we, and where do we need to go?

- If we think back about being on the boards of these organizations, being active in the Urban League, the NAACP, the League of Women Voters, the campaigns, what's the overriding theme?

- Service.

(soft music) (gentle music)

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story | Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Special | 30s | A reflection on the life of freedom fighter and civic leader Dr. Josie Johnson. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

HOPE IN THE STRUGGLE: The Josie Johnson Story is a local public television program presented by TPT