Imaging Live Cells Under Viral Attack

Special | 54m 16sVideo has Closed Captions

Nathan Sherer explores how imaging live cells can aid in the understanding of HIV.

Nathan Sherer, Assistant Professor at the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, explores the advances in live cell imaging technologies, leading to a clearer understanding of how HIV-1 and other viruses attack human cells. This technology is being used to advance new antiviral strategies.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

University Place is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

University Place is made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Imaging Live Cells Under Viral Attack

Special | 54m 16sVideo has Closed Captions

Nathan Sherer, Assistant Professor at the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, explores the advances in live cell imaging technologies, leading to a clearer understanding of how HIV-1 and other viruses attack human cells. This technology is being used to advance new antiviral strategies.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch University Place

University Place is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Experts share their groundbreaking research and insights on big scientific questions. Enjoy lectures from the "Wednesday Nite @ the Lab," hosted by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where researchers and faculty discuss discoveries across diverse fields — from medicine and ecology to astronomy and agriculture.

Human Stem Cells 25 Years Later: Where are We?

Video has Closed Captions

Su-Chun Zhang reflects on the history and future of human embryonic stem cell research. (56m 35s)

What Are Cells and Could They Be More?

Video has Closed Captions

Scott Coyle shows how living cells can be technological tools, beyond just "biology." (58m 16s)

Chemical Glassware as Functional Sculpture

Video has Closed Captions

Daniel Kelm explores the history of chemists and their glassware. (53m 34s)

The Case for Blueberry by Cranberry Hybridization

Video has Closed Captions

Fernando de la Torre describes a perfect blueberry by cranberry hybrid fruit. (55m)

Breeding Tree Crops to Fight Climate Change

Video has Closed Captions

Scott Brainard describes his research improving tree genetics to mitigate climate change. (55m 53s)

Investigating Glacial Lake Yahara

Video has Closed Captions

Eric Carson shares research on the ancient lake which covered the Madison Four Lakes area. (36m 46s)

Wisconsin Weather Safety and You

Video has Closed Captions

Kurt Kotenberg explains how to prepare for severe weather, and how to keep safe. (54m 30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Ben Ullerup Mathers and Gina Mode share the history of butter and how it's made. (52m 34s)

Wisconsin’s Lost Coastal Communities

Video has Closed Captions

Amy Rosebrough describes 19th century communities along the eastern shores of Wisconsin. (47m 33s)

Video has Closed Captions

Andrea Strzelec gives a basic and practical description of what energy is. (45m 14s)

The Legendary Foundations of Ancient Vietnam

Video has Closed Captions

Nam C. Kim presents archaeological research on Vietnam, including the ancient city Co Loa. (55m 52s)

Pollutants, Parasites, and You

Video has Closed Captions

Jessica Hua looks at how pollutants in the environment influence natural ecosystems. (56m 34s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

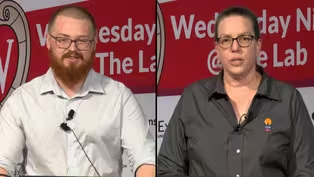

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Welcome, everyone, to Wednesday Nite @ the Lab.

My name is Fiona McNamara.

I'm a second year undergrad student here at the UW Madison.

I work for Tom Zinnen, who couldn't make it this evening.

We do this every Wednesday night, 50 times a year here at the UW Biotechnology Center.

Tonight, it is my pleasure to introduce to you Nathan Sherer from the Department of Oncology.

He is originally from Bismarck, North Dakota.

He went to Bismarck High School there, and then he went and got his undergrad in Grinnell College, which is in Iowa.

Then he went to Yale to get his PhD, and after that he post-docked in London, England, for five years until he came to UW-Madison in 2011.

Tonight, he will be talking about imaging live cells under viral attack.

Please join me in welcoming Nathan Sherer to Wednesday Nite @ the Lab.

[applause] - Thanks for being here tonight.

So yeah, my name is Nate, and I'm an Assistant Professor affiliated with the Department of Oncology, which is also known for the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, many of you will know.

And I have a joint appointment in the Institute for Molecular Virology, which is on the other side of Henry Mall in Robert Bock Laboratories on Linden Drive.

And tonight I'm going to tell you a little bit about-- It's mostly an excuse to try to-- You know, as the research goes on, you start to lose touch with old things, and I really wanted to sort of go back through my old favorite movies and share them.

[laughter] Because I miss them and I don't get to talk about them all the time.

And hopefully, you known, through this I'll be able to, you know, tell you a little bit about virology on this campus, which is extraordinary.

I know Dave O'Connor was here a couple weeks ago talking about Zika.

We have an almost second-to-none community of virologists on this campus.

I'll tell you a little bit about why we care about viruses and virus-host interactions and what we're trying to learn.

I'll tell you about how we've gone about trying to build fluorescent viruses in cells that we can image using live cell imaging.

So that's where the viral cellular attack and interplay comes in.

And I'll sort of finish with, you know, what my vision for the future in terms of what we can now do in terms of sort of developing a multi-variant, high content, multi-color imaging system for trying to learn very comprehensive things about how viruses act in cells, and how they spread from one cell to another.

Okay, so viruses, why do we care?

Of course, viruses impact the health of humans, animals, and plants.

So this is just kind of the last five years.

Things that have-- Many of these things have popped up.

Some of these things you know that afflict us on a regular basis.

So we have seasonal flu, common colds, all sorts of respiratory infections, stomach bugs, chickenpox, herpes virus-type afflictions that are latent and stick with us for lifetime, come back and cause shingles.

Things like this.

I'm going to mostly talk about HIV/AIDS because that's the focus of my laboratory.

HIV continues to be a massive problem and is still one of the, I think, number six in terms of the top killers on the planet despite all the progress we've made.

And then all these other guys which have been popping up in recent years as the world population has grown, as we've started to commingle with new environments that we hadn't before, as viruses continue to change and feel out new evolutionary space.

It turns out that some of them start to cause human diseases, and that's, of course, what we saw with Ebola last year, and then this year's hot topic of Zika.

Okay, so this is going to be kind of the only dense text slide.

But just to run through, you know, some global perspectives on what are some of the big viruses that we worry about at present.

So, HIV currently infects more than 34 million people on the planet.

There have been about 70 million infected since it showed up in the late '70s.

And it still causes more than one million deaths per year even though we now have pretty good drugs that can control this infection.

Hepatitis B and C viruses are crazy.

More than 200 million people are infected at any one time.

And roughly one million deaths per year.

They both establish or can establish lifelong chronic infections that can lead to liver disease and cancers.

We're all full of different herpes viruses.

I had infection mononucleosis when I was in college and a raging case of chickenpox when I was nine caused by varicella-zoster.

A variety of herpes virus circulate in humans and cause different diseases.

Birth defects, cancers, all sorts of issues.

Every year we're afflicted by new versions of influenza.

Roughly 250,000 deaths per year with pandemic potential.

So we're always very concerned about flu.

And rabies is always something that's just sort of terrified me because it's almost universally fatal.

It's very rare in the United States to now get a rabies infection but it does happen, and it still, worldwide, leads to about 60,000 deaths per year.

And then, we have these emerging viruses.

So, each year, there seems to be a hot new virus which is causing problems.

Fortunately, with the exception of Ebola in 2016, these viruses, such as Ebola; Marburg, which are these Filoviruses; SARS and MERS, which are members of the Coronavirus family; Zika, which is all the rage at the moment and is a Flavivirus.

And chikungunya is one that we haven't talked about too much, but this is now prevalent in the Bahamas, and it's also mosquito-borne like Zika.

And there's thought with climate change that this will be one that will be quite prevalent, especially in the south, over the next few years.

It causes a debilitating, long-lasting disease that sort of resembles rheumatoid arthritis.

So, relatively few deaths from these emerging viruses, but they keep coming.

They keep surprising us.

When I was just out of college, I worked in a lab that studied Coronaviruses.

The virus we studied was called murine hepatitis virus.

It was the only virus, the Coronavirus, that was known to cause disease.

And my boss couldn't get funding because nobody cared about the mouse.

So after I left the lab, the NIH basically called her up after SARS showed up because now we had a Coronavirus that had showed up in people and was causing disease.

And they said, "How much money do you need?"

[laughter] So this is just to reinforce, sort of, this need for basic research.

You know?

We need to study viruses even if we don't think they're important because we really don't know what's coming in the pipeline.

And what will the future bring?

This is sort of an estimate.

It's a bit dated now.

This is almost 10 years old.

But, currently, there are at least 150 viruses that infect humans that we know about.

And, you know, the prediction is, you know, over the next 10 years we'll probably identify upwards of 50 more.

And, again, as viruses fill evolutionary space and encounter people in different places and in different ways than they have before, there's always potential for a virus to find a new niche, cause a new disease.

Okay, so I'm just going to put on my ambassador hat for a couple of minutes and talk about virology on campus.

So I'm affiliated with the Department of Oncology.

So that's cancer.

Why do we care about viruses?

Well, roughly 15% to 20% of human cancers are caused by viruses.

So I named a couple of the viruses that cause cancers.

So different herpes viruses, hepatitis B and C viruses are tightly linked to human cancers.

And the McArdle Laboratory, a famous building right behind us, was really a hotbed for studying viruses that cause cancer and understanding how they worked in a variety of animal systems.

And, as many of you know, McArdle has now vacated this famous building and has moved to WIMR2.

And it's about the-- It's the 75th anniversary of the McArdle Laboratory.

And among many landmark discoveries that have been made at McArdle, such as Harold Rusch showing that UV light causes skin cancers, the Millers showed how carcinogens lead to cancer, Charles Heid-- I'll come back to Howard Temin.

But Charles Heidelberger discovered 5-FU.

This is a very potent anti-cancer therapeutic that's still very commonly used in the clinic.

And Bill Dove, who's still very active in the department.

He's emeritus but continues several projects.

He developed the very first mouse model colorectal cancer, suitable for drug testing.

But, in terms of viruses, this all went back to Howard Temin, and this is another fortuitous basic cancer research story where Howard started his research studying a chicken virus that caused a transmissible cancer called Rous sarcoma.

And he was-- Over time, it was found that Rous sarcoma was a virus that was part of the family called retroviruses.

These are viruses that are able to inject their genomes into the cells, and we'll get into the details in a minute.

In 1975, Temin won the Nobel Prize for discovering a reverse transcriptase, which is an enzyme.

The retroviruses are RNA viruses, they have RNA genomes, but they convert that RNA genome into double-stranded DNA that looks just like the DNA that's inside all of our cells.

And then it has a sophisticated mechanism for injecting that DNA into the genome so that every single cell that gets infected inherits a copy of that virus.

And Rous sarcoma virus had picked up a cellular gene that it was carrying with it, which was called SAR kinase.

And any time it would infect a cell, it would overexpress this kinase, and it would cause the cells to replicate more quickly.

And that led to rapid cell proliferation and the development of sarcomas in chickens.

He did all of his research, and the reason that he won the Nobel Prize is because this idea of reverse transcriptase through what we call the central dogma of molecular biology on his head, where in the 1950s we knew about DNA, we knew that DNA encoded messenger RNAs, and we knew that messenger RNAs were translated into proteins.

And that's sort of, you know, how cells worked.

And, from there on, you can make all the enzymes and structures that you needed in order to make a cell and then form a tissue and then make an organism.

What Temin showed is that this RNA virus could actually turn that mechanism on its head and take an RNA, turn it back into DNA, and then that DNA could be inserted into the genome.

And this discovery has been massively useful for biotechnology because now we can take messenger RNAs that we can isolate from cells and turn them into DNA copies that we can then store in the freezer and replicate and use over and over.

And, perhaps most importantly, it turned out when HIV came on the scene in the early '80s that it was of the same family of viruses as that chicken virus.

And it required the same reverse transcriptase activity.

So what Howard had taught the world about reverse transcriptase led very quickly to the design of drugs that turned out to be quite effective for inhibiting HIV.

So this discovery in a chicken virus ultimately led to, you know, saving millions upon millions of lives.

So this is McArdle now.

Temin really devoted a lot of his energy in the '70s and '80s to building a core of virologists in the department.

So our current chairman is Paul Lambert, who studies human papillomavirus that causes cervical cancer.

At least in this slide we feature Bill Sugden and Shannon Kenney and Rob Kalejta and some other guy who study-- These guys study Epstein-Barr virus, which causes lymphoma and mononucleosis.

Rob studies HCMV that causes birth defects.

It's another herpes virus and glioblastoma.

We have many other prominent virologists in the department, and we interact with many fabulous other scientists studying cell signaling mechanisms involved in cancer and using genetic systems to try and determine the origins of cancer.

And my other home is the Institute for Molecular Virology.

So that's Bock that was I referring to earlier.

And there we're just all about viruses.

So this department was built by Paul Kaesberg, who passed away in 2010, but was one of the world leaders in understanding and characterizing small RNA viruses, and with a prominent role from Roland Rueckert, who is one of the pioneers of understanding structural biology using viral systems, with an emphasis on Picornaviruses such as polio and the rhinoviruses that cause the common cold.

So, at the IMV, we have many fabulous scientists.

Our chairman is Paul Friesen, who studies Baculovirus, and Paul Moberg, who continues work on Picornaviruses.

Paul Ahlquist, who's one of the world's most well renowned RNA virologists.

Rob and me, the three of us are also linked to McArdle and the oncology department.

And I just wanted to set, you know, our mission is to conduct research and do a lot of training at the IMV.

So we want to serve as the focus for virology on the campus.

We hold a weekly seminar series.

If anybody's interested, it's open in the biochem building across the street at noon, all about viruses.

And we play a big role.

Every five years we host the American Society for Virology meeting in Madison at the Monona Terrace.

And a couple weeks ago, we hosted a Grandparents' University, both out at McArdle and at the IMV.

Here's Ann Palmenberg teaching alumni and their grandkids about viral structures.

Kelly Waters, a post doc in the department teaching them about sequences.

So just an advertisement, if you're a grandparent, an alum, a grandparent, or know of one, that should be pretty fun.

And I'll show this again at the end of the talk, but these are just if you're interested in virology on campus.

We also fantastic virologists in the department in the Veterinary School, the Department of Medical Microbiology, Immunology and also in the pathology and laboratory medicine.

Okay, so HIV/AIDS, I mentioned more than 35 million people infected globally.

We still have two million new cases per year and more than one million deaths.

Despite huge efforts, we still do not have a vaccine for HIV.

We have one person out of 70 million infected over the history of this pandemic who we think is cured, who has been off drugs for several years with no recurrence.

That cure involved a stem cell transplant and some very clever gene therapy type considerations.

So it's not a practical cure for anybody else.

We have great drugs since the mid-'90s that keep people alive and to have a happy and healthy life.

But the problem remains getting everybody on drugs, getting everybody adherent to their drug regiments, keeping the drugs cheap enough and accessible.

So it's still going to be an enormous task to eradicate.

The current goals of the CDC, the NIH, and the WHO and the UNAIDS are this 90-90-90 idea, where 90% of the people who are infected with HIV are going to know that they're infected.

It means more and more people have to be tested.

90% of those people who are positive are going to have access to drugs and are going to stay on those drugs.

And of those 90% who are on drugs, they're going to have to have their viral load suppressed.

If that works, the math looks really good that we could have an AIDS-free generation over one to two generations.

So that's the current goal for between 2020 and 2030.

So I'll point out that, you know, typically these days we think about sub-Saharan Africa.

This is where the most of the cases of HIV and most people are dealing with HIV/AIDS.

But I'll also point out that, you know, we don't talk about it much anymore, but we still have huge numbers of people who are HIV positive in the United States.

Well over a million, and the number continues to grow.

And it's one of these problems that is particularly bad for underrepresented minority communities that have limited access to healthcare.

Okay, so now the crash course in viruses.

What makes a virus a virus?

So, effectively, the simplest way to think about viruses is that they make things called virions, which are replicating nanoparticles.

So, at the nano scale, about 30 to 300 nanometers, is kind of a common size of the virions that we study and think about.

Virus came from the Latin for "poison."

It was first used in reference to rabies infection in the 19th century.

Around that time, it was found that you could filter out bacteria from animals who had things like rabies or this chicken sarcoma virus that Howard Temin studied.

And you could still transmit serum and transmit the disease, which meant that there was something smaller than bacteria which we couldn't access, which was capable of causing disease.

Sort of a terrifying concept at the time.

And then, I'm a cell biologist or I like to think of myself as a cell biologist, so the coolest thing about viruses is that they're obligate, so they're parasites.

They're not capable of replicating on their own.

They have to find a cell in order to replicate.

They all have their own genomes and their own genes.

They make their own proteins and their own enzymes.

But they need cells or they can't do it.

So, this is the transmissible unit of a virus, which is known as a virion.

Even though, in the newspaper, they'll show a picture of this and they'll call it a virus, remember to always correct them and say that's a virion.

The core of a virion is there's a genome so it's nucleic acid.

So, it's either DNA or RNA.

It can be double-stranded or single-stranded depending on the virus.

There's every permutation on the planet because there's so many viruses on the planet.

They all have different ways of operating.

This is the human papillomavirus that causes cervical cancer, and other cancers can also, different versions of it can cause warts on your skin.

And so papillomavirus has a DNA genome that looks quite similar to the genome in our cells that's wrapped up on these things called histones.

And it's packed in a capsid core, which is shown here, and that protects the genome.

And the idea here is that this is Uber of the virus.

The virion can take the infection from one cell to another.

So, if you want to understand the virus, you have to understand the cell.

And viruses evolve to understand cells better than we ever could, which makes them really good tools for research.

So the virion needs to get inside a cell.

So this is a depiction of an animal cell.

You see the nucleus here where the DNA is stored.

All the organelles in the cytoplasm that are there for metabolism and processing proteins and making things work.

So, again, this concept where the viruses can't move, generate energy, synthesize proteins outside the cell.

This is an age old debate over whether viruses are alive or not because if this guy is on its own, it can't replicate.

It doesn't have everything that it needs.

In the context of a cell, some people argue that a virus is alive, but you kind of end up with this metaphysical concept of what is-- If it's really a living organism or some other kind of organism.

So, what we've learned, especially with new sequencing technologies, is that there are an insane number of viruses on the planet.

So every virus needs a cell, and the world is full of cells.

So we're made of cells.

Plants are made of cells.

The soil is full of cells.

The ocean is massively full of cells.

It's just teeming with bacteria and other microbes.

And every one of those is potentially a host for a different type of virus.

So it's now predicted that there are at least 100 million different viruses on the planet.

Most infect bacteria in the ocean, and a recent realization is that these infections of bacteria are actually involved in a huge amount of nutrient turnover on the planet.

So it'll probably play very important roles in terms of maintaining the viable ecosystem for the beautiful planet that we live on.

In mammals, there are at least 320,000 different viruses currently predicted.

And I mentioned this earlier, we know that there's at least 150 viruses that infect humans.

Not all of them cause diseases.

Some of them might actually help prevent diseases.

So it's a complicated world when it comes to viruses.

And this is-- I saw Jean-Yves walk in, who is Jean-Yves Sgro who has worked for the IMV in the Biotech Center and has done all these amazing illustrations of different viruses capsids and different virus structures, which are accessible at this great website called Virus World.

So if you get a chance, check it out.

These are some examples of the beautiful structures that viruses come in.

Many of them are icosahedral in structure and spherical.

Many of them end up making what we call spherical or filamentous nucleocapsids, which are linear.

There's every sort of shape and size that you can imagine.

And then on top of that, beyond the protein shell and the genome, you can get all these accessories.

So some of the viruses have tails and spikes.

Many of the viruses that we're most concerned about, Influenza, Ebola virus, HIV, they have a lipid envelop.

so they steal some lipid from the surface of the cell and surround themselves.

They add an extra layer of protection on top of the protein that protects their genome.

So there's HIV.

It has a beautiful protein conical core that coats two RNA genomes on the inside.

And then that's surrounded by a lipid.

And then, this is Ebola, which has this long filamentous nucleocapsid surrounding an RNA genome, but it's also wrapped in a lipid.

So, again, a huge amount of diversity in different evolutionary strategies that viruses have adopted to do what they do.

Okay, so what happens in the cell?

So I'm going to use Ebola as an example.

This is an image from a relatively recent review on Ebola replication.

And, basically, what needs to happen, viruses, they have relatively small genomes since they're much smaller than cells.

So they have enough to replicate themselves, but everything else has to come from the cell.

The first step is delivery.

So, for Ebola, these first four steps over here are delivery.

It's going to bind to a cell.

It's going to be taken up into the cell, and it's going to find a way to get into the cytoplasm where it can access all the enzymes that it needs to replicate.

Two is decoding, where the viral mRNAs-- So the genes in the virus make messenger RNAs that are made into viral proteins to make new viruses.

And then, number three is the replication.

So, here we see protein synthesis and things starting to come together.

The genomes are being replicated down here, step five.

And then, finally, everything has to come back together in kind of this symmetrical process, make a new virus, or new virion, sorry, and then, move on to the next cell.

So, viruses are very specific in terms of the cells that they can infect.

They've adapted to certain cells.

That's why we don't-- Your dog might get a canine parvovirus, but it won't be able to infect you because you don't have the right cells for that virus.

And all viruses must involve a strategy to move from host to host.

Some use blood products.

Some will-- Some prefer sneezes and door handles.

And then, within the tissues, they have to have ways that they can circulate in order to make enough copies to move on to the next person.

Okay, and then, I really like this other point that a lot of viruses really ravish their cells.

So they're kind of smash and burn.

They go into the cell, they replicate, they get out, and they trash the place.

And a lot of double-stranded RNA viruses do this and also positive-strand RNA viruses.

And I make this point because for HIV, that's not really the case.

HIV, because it integrates its DNA into the genome, it really wants to keep the cell happy because it's going to be its home for a while.

And this is especially true, this is why we can't get rid of HIV because once you're infected with the HIV, it inserts its genome into the cell forever, and it hides out in those cells so that even if you're on drugs, if you ever go off drugs, there's going to be a few cells that are latently infected or persistently infected, and then the virus will come raging back.

So, in terms of Madison real estate, some people are more invested in their homes than others.

So, we have these smash and burn type viruses and the others that are very committed to keeping the cell happy and healthy.

And then that has consequences for the pathogenesis.

Okay, so seeing is believing.

How do we see the viruses?

So, if you look at your hand, there's a bunch of cells there, but you can't really see them.

You can see them, but they're all stitched together.

You can't see an individual cell unless you have a microscope.

It's too small.

So an average cell is probably about 10 microns in diameter.

Bacterium is about tenfold smaller than that.

About a micron.

And then, a typical virus is about 10 times smaller than that.

So we can't see individual cells in our hands, in our saliva, anywhere.

Kind of the exception would be eggs, which are really big cells.

But the-- We can't see most bacterium unless we have a microscope.

And then viruses are a severe challenge beyond that.

So how do we deal with that?

Traditionally, the way that we've studied viruses, especially up until the 1980s, was using electron microscopy, where the idea is we had technology, and some of this was actually developed by Paul Kaesberg in the IMV, where we could take viruses, or what we thought were viruses, and put them on to a very thin grid, coat the grid with metal, and then, bombard the sample with electrons.

And whatever light got through could then be detected, or whatever electrons got through could be detected, and then leave an image of what's there.

So that's how the viruses were originally detected and characterized using the electron microscope, and you could get resolution data to 120 nanometers.

This is the T2 bacteriophage, which is a famous virus of bacteria.

You can see it looks like a lunar lander module.

So the genomes up in this capsid shell on top-- I hit the button.

And then there's this long syringe-like extension or tail, and then it's got these little landing pads that it uses to latch onto the bacteria and inject its nucleic acid.

It's almost designed like a syringe.

This is tobacco mosaic virus, one of the most famous plant virus early viral model systems.

And it actually makes long helical capsids.

The capsids that are about 300 nanometers.

This is one of our images of HIV coming out of a cell.

So this is human cell making envelope HIV particles.

You can see the tiny little conical capsid in the interior and the lipid envelop on the outside.

And then, recently, in the last 10 to 15 years, we've made huge advances using a technique called cryo-electron microscopy with tomography, or cryo-EM.

And the idea here is that you can make a bunch-- One, you can freeze the samples instead of using harsh fixatives, and you can maintain very good structure of viruses.

So you can maintain the lipids and the proteins, keep them really happy, and then you slice them up very carefully, put them on an EM grid, and you take a picture of each one of the individuals.

So it's like slicing up an apple.

You take a picture of each individual slice and you turn it slowly in the beam so that you get a whole bunch of different images from different angles of that apple slice.

And then you can computationally put them all back together and actually get a three-dimensional image of what's there.

And this has gotten so good now that the detectors can now achieve single nanometer scale with some virus particles.

So some of the structures would be down to 2.6 angstroms which used to be the only way we could get that kind of resolution is with crystal structures.

So it's an exciting time for EM, and it continues to advance even though it's a very old school technique.

All right, so, in the '80s, people started coupling fast cameras with microscopes and moved into the age of time lapse video microscopy.

And this is my favorite thing.

So, we finally get to a viral video.

[laughter] So, this is a movie that I did with Kelly Waters and Ann Palmenberg, who study human rhinovirus A in this case, which causes the common cold.

And the idea here is that each one of these individual blips is a cell.

So these are HeLa cells from Henrietta Lacks that we use quite frequently for our research.

And we're going to infect them with the rhinovirus and see what happens.

And so this is about 15 hours of imaging.

And what you can see is the cells are not very happy.

So this is a smash and burn virus.

This is a virus that does not care about itself for very long.

It just wants to make copies of itself, make the cell explode, and release new copies of the virion.

So we can't see the virions.

They're too small, but we can see what happens to the cells.

And now, you can imagine this is what's going on in your lungs every single time that you have a cold.

So, not a very nice virus.

And then, I really love this movie.

This is from Paul Friesen, who studies Baculovirus.

This is an insect virus.

I'm glad it doesn't infect humans because what it does is it basically-- It causes caterpillars to melt.

It's really ferocious.

Its replication cycle is that it will actually reprogram the caterpillar to climb to the top of a tree.

It will make the caterpillar melt, and then it'll drip down onto the bottom leaves and then other caterpillars will eat it.

And that's how it moves from one caterpillar to the next.

It's absolutely insane.

So these are insect cells taken from drosophila, fruit flies, and they're infected with Baculovirus.

And this is, I think, yeah, 24 hours of imaging.

And you can see what the Baculovirus does to the cells, which is extraordinary.

So the cells are moving around.

You can kind of see a big sphere in the middle.

That's the nucleus.

And they start to bleb.

That's a sign that cells are getting sick, and they're thinking about dying.

And then we're about 12 hours now.

Whoops.

Oh, man.

Now I've got to restart the whole thing.

I can cut to chase.

And the virus starts cranking out protein like crazy.

And Baculovirus actually turn out to be a wonderful tool for making protein for biotechnology purposes because it completely hijacks cells, uses all the resources in the cell to do its own bidding.

And what you see here are huge-- These are called occlusions of viral capsid proteins in the interior.

They make these big and remarkable cubes in the interior of the cell.

And you can see at the end of the movie, you know, the cell looks nothing like it did at the beginning, and it's pretty drastic transition.

Okay, so HIV, as I mentioned, is not so disruptive.

So you don't learn much from studying HIV just with a light microscope.

You've got to have a trick in order to put a label into the virus so you can actually see it.

So I've kind of shown you this earlier, but the basic 30-second life cycle of HIV is that it's a virus that has two copies of an RNA genome, has this lipid envelop, it recognizes a receptor on the surface of select cell types, and releases the capsid into the cell.

This is Howard Temin's discovery is that the RNA genome, which is red, gets turned into blue DNA, shown here, and then that gets taken up into the nucleus and stuck into our genome.

And then after that it really pretends to be a cellular gene.

So this is a really clever virus.

It just acts like all the rest of our genes.

It tells-- It uses our enzymes to make messenger RNAs that are then taken out into the cytoplasm to make new proteins, and then those proteins make new virions and they go on to infect other cells.

Okay, so how do we study HIV?

And here the key breakthrough was in the '90s where it was identified by a few different groups that these jellyfish and other organisms in the ocean had fluorescent tendencies.

And a few of the groups were able to isolate the genes that made them fluoresce.

And the most famous one is this one called green fluorescent protein.

Most of the work on this was done by Roger Tsien, who won the Nobel Prize with two other groups for this discovery.

And their clever idea was, well, if we could isolate this fluorescent protein, we could attach it to whatever we want, and then we could put it under a microscope and we could do just what the jellyfish does, is we could use that fluorescent protein to detect light and then emit a different wavelength, which is the essence of fluorescence, and we could track that protein in the interior of the cells.

And this would open up all of cell biology because now we could actually see what's going on inside a cell, not just watching cells die.

So when I was in grad school, we started engineering fluorescent viruses.

There were a few other groups that were doing this as well, but I think we were the best.

[laughter] But the idea here was if we could make that capsid, so that cone in the center of HIV or other retroviruses, green, for example, and use other fluorescent proteins.

So by the time that I was in grad school, there was a whole rainbow of different fluorescent proteins that could be used, so you could actually make two- or three-color viruses.

We could make a fluorescent envelop.

Then we could actually look inside cells, and we could see how the viruses came out of the cells, how they went into the cells, and how they moved from one cell to another.

So, that's what we set out to do.

And this work was done with Walther Mothes at Yale University when I was a graduate student.

So we engineered murine leukemia virus, which is a virus very similar to HIV.

It has a very similar lifestyle.

It's also a retrovirus.

We did the same thing for HIV, but most of our emphasis was on MLV.

It was a bit safer and easier to work with as a model.

And we fused the capsid protein, which is called Gag, which makes this shell in the center of the retrovirus to green fluorescent protein.

And then there's a glycoprotein that the virus makes that sticks on the outside.

So it's the spike protein.

We made that red.

We found a place to insert the fluorescent protein that wouldn't screw up the virus.

And then, actually, in the back-- So, we could spin down those virions that were secreted from cells and make big tubes full of these fluorescent viruses that we could then throw on cells.

So this is work from a post doc in Walther's lab, Mike Lehmann.

One of the early cool things that we found was this phenomenon called "virus surfing," where this is an uninfected cell, which is green.

So, it's fluorescent green so you can see it.

And it turns out, when you start looking closely at fluorescent cells, they're covered in these actin-rich protrusions.

So, you know, actin is the protein that runs our muscles, but it's also used in cells to guide a lot of motility in different functions.

So you see these long fibers sticking out.

Those are called filopodia, and one of the things that we characterize, when you added virions to cells, they would bind to these actin-rich filopodia and move inward.

And we can show by electron microscopy that the virions are actually on the outside of the filopodia.

So they were actually surfing along the outer surface.

That's why we call it surfing.

And then, you know, kind of our overarching model for why the viruses did this with several additional studies was that they would use these filopodia to get in towards-- Retroviruses want to get their genomes toward the nucleus.

So this allowed them to directionally move from the outer space towards the inner space.

And we can see them co-localizing with these things called endosomes, which are vesicles that take things from the surface of the cell into the interior in order to direct things inward.

So, I never published this but this was one of my achievements where I think, you know, I was probably the first person to ever see a retrovirus actually budding and forming in real-time.

So these are individual virus particles forming on the surface of a cell.

You can see the cell moving and kicking around.

The green signal is the Gag protein, and every now and then it all coalesces together to form a little dot.

And you can see an example of that here.

And then you can see there's an example of some other virions stuck on the surface.

And there's one, when it loops around again, about here that pinches off and floats away to go infect another cell.

So, anyway, this was a useful tool for sort of starting to understand how fast viruses were made, how they got out of the cell, where it happened.

It was pretty clear from these types of movies that it was happening at the surface plasma of the cell.

At the time that wasn't known.

And how they get into the interior of the cells.

And the other one that we were very interested in is how do viruses move from cell to cell.

So, you know, you guys are comfortable with the virion idea now, and it turns out there's multiple ways that virions can move from one cell to another.

There's what we call the cell-free mode, which, you know, with an HIV infection probably happens in the blood stream.

There's lots of little virions that are moving around and circulating and looking for new host cells.

So they can float through space and then infect a new cell.

But then there's also this notion that in dense tissues, if you have a cell that's infected with a virus, such as HIV, and it encounters a cell that's uninfected, the two cells can actually interact to form intimate linkages, which we call virological synapses.

And at these sites of contact is very efficient for infection to move from one cell to another.

So we set up some systems to try to visualize this in real-time.

And here's my favorite movie ever.

So what you see here is an uninfected cell.

Here's an infected cell.

It's making little red murine leukemia virus dots.

And when the two cells interact with each other, they grab onto each other.

You see the little dots form at the site of contact.

And then they go running over from one cell to another.

So this entire movie is about 30 minutes, but it almost looks like a machine gun.

The virions are being shot over to the uninfected cell.

And then this one is kind of dramatic.

It's a bit bright up here.

I don't know if I can fix the light, but I didn't have any instructions.

[laughs] But anyway, this was, in terms of folk stories, this was a nice movie because it shows the-- I lost my cursor.

Oh well.

It shows the-- It shows an infected cell making green viruses in the center with two uninfected cells in either direction sort of pumping viruses in both directions.

And if you're looking for-- Here's my cursor.

Okay.

If you're looking for a good date movie, there were actually- a bunch of our movies were used as the intro to this movie about HIV in the African American community.

It's a murder mystery by Bill Duke in the intro credit.

So that was one of my most exciting achievements.

[laughter] I'm in the movie database with the credits.

So, check out "Cover," directed by Bill Duke.

Okay, so now we're working on, since we've come to Madison, when I did my post doc, I didn't do any imaging, or very little, you know?

I learned all sorts of other techniques.

But I worked a lot on RNA trafficking and HIV gene expression, and everything was very focused on HIV.

So, when I got here, the thought was that technology has progressed to the point where we now have microscopes where we can-- A lot of those movies I showed you were half an hour, two hours.

Now, we can keep cells alive for days, and we have automated stages where we can look at 24 different conditions for three or four days.

We can look at multiple rounds of infections.

We can look at how the cells are interacting.

We can look at six different colors because of all these different fluorescent proteins.

And we can use the computer to start to make these very elaborate models for what's going on.

So, I'm getting late so I'm going to go through this relatively quickly.

But one of the systems that we set up was we wanted to understand HIV gene expression, how we make a virus particle, and kind of the overarching goal to this is that we don't have any drugs that shut off HIV virion production.

All the drugs that we have in the clinic kill the virions after they've been made.

So if we could figure out ways to shut off making new virus particles, that would be useful.

And we know a lot about how this works, but not enough.

Still a lot of questions.

So we set up this system where we could see HIV genomes in the nucleus using one color.

So we can make green RNAs that are going to be exported from the nucleus into the cytoplasm.

They're going to encode a blue Gag protein.

I brought this one up earlier.

That's the protein that makes the capsid shell that makes the virion.

So this is a budding virion at the surface of the cell.

And then we're going to use this red protein that I haven't introduced yet, which is called Rev, which is an activator of-- It turns on gene expression for the virus.

So we had a system where, if we put in the red protein, that would take the green genome out of the nucleus.

That would make the blue protein, and then the whole virion would get made at the cell surface.

So we wondered if we could model this using three colors.

So we made this virus, which we called three-colored visible HIV, and then this is what it looked like in the cell when we could finally figure out a way to image for 24 hours without killing the cell.

In order to do that, you need cells that are very cooperative and that don't move and very hardy and don't mind being blasted with light for long periods of time.

And again, HeLa cells are very good for this.

So, what you see in this movie is that, at the beginning, we're starting to see the red protein, and that's the protein that's turning on gene expression.

The green signal that you're seeing in the center circle is individual genomes inside the nucleus.

And then, over time, that green signal is going to move into the cytoplasm, and that's where translation occurs and proteins are made.

So we're seeing nuclear export of messenger RNAs and translation.

And then, at the end of it, we start seeing bright blue and green dots, which are new virions being made at the cell surface.

So, it worked great.

We can see the entire-- All the explosive events that occurred during HIV virion assembly.

And, really, we're visualizing the central dogma.

We're seeing RNAs being made.

We're seeing them exported from the nucleus.

We're seeing translated to make protein.

And then we're seeing the proteins do something, which, in this case, is make a virion.

And we've kind of set up this systems-based approach where we can do these movies on thousands of cells simultaneously, and then we ask the computer to start to extract information from the movies.

And this is work led by Ginger Pocock, with help from Jordan Becker in the lab.

And using advanced image analysis, we can then extract all sorts of intimate details about what's going on in each single cell and then use that to build a model for how we think that virus assembly and virus particle production works.

So I moved quickly through this, but this has allowed us to build a spatial-temporal model for all these different aspects.

So, between zero to 15 hours, we see genomes being made in the nucleus.

They get exported to the cytoplasm.

We can measure very carefully the rates of Gag synthesis.

And then we can see, in this movie, we can see when virus particles start to be made very specifically.

And now we're using this for a lot of different things.

We're learning, using it to study mechanistic aspects of the virus.

So, what cellular proteins and what viral proteins make this whole thing work and how can we perturb that in a productive way.

We want to set this up as a high content screening platform where we could, you know, use drugs and not only know if they're blocking HIV replication but specifically at what stage are they blocking the pathway.

And we have great collaborators on campus to develop new image analysis tools because this is really the future where we can use imaging to extract as much information as possible from movies, effectively, and tell us lots of things.

And these are just some additional fun viral videos.

So, in terms of understanding the regulation of this export pathway, what you see here are HIV RNAs.

We've been testing different cellular factors, which we think might be involved in the gene expression pathway.

And when I turn this on, you'll see the HIV red protein come up in Rev, and that's the protein that turns on gene expression.

But we've also put in a protein that you can see that's called Sam68, and when we do that it makes everything basically explode out of the nucleus.

So we've accentuated this spatial nuclear export activity that nobody's ever seen before.

And I'm very excited about this because it implies that-- We always thought that mRNAs in the nucleus just trickle out of the pores.

But here they all move into a big focus.

We've also been able to use this system to identify new activities.

So what you see here are two cells that are actively-- A cell that's dividing into two daughter cells.

So the red signal here is microtubules, which form the spindles that take the chromosomes into the two new cells.

And the green signal is the viral RNA, and we found a specific viral element that clumps RNAs very specifically onto microtubules.

And we honestly don't have any functional relevance for this, but it's a pretty movie so we're trying to understand why would RNAs want to go to the end of microtubules in these sub-organelles called centrosomes.

And then the other thing that we're working on that I'll finish with is the most important thing is understanding how HIV spreads in tissues and how it establishes long-term persistent infection.

So, you know, HIV is very good at hiding in dendritic cells and tricking immune cells to pass the virus on from one to the other.

So we've been trying to make these-- We've been trying to take a step back and set up systems where we can make scenarios that look like tissues and then mix cells together that are infected and uninfected and use fluorescent markers in order to track the virus moving over time.

So what you see here, the red cells are infected with HIV and the green cells are uninfected.

And they're moving, and we've developed software where we can track how the cells interact, when they become infected, all these different attributes of the infection system.

And then, hopefully, we can develop this into better systems for finding ways to actually block the spread of infection.

This is just to show that we can measure stuff.

[laughter] And by measuring these things, by making it quantitative, we can come up with new models for how we think the system works.

So the quantification and the computational aspects are very important.

And so, in terms of cell-cell spread, our initial studies have allowed us to develop this model for how we think remodeling of the infected cell in red allows it to basically grab on to uninfected cells and then make them do their bidding.

So I'll summarize and just say that UW Madison is a fantastic place to study viruses.

If you're into viruses, this is the place to be.

HIV/AIDS remains a huge global and local problem.

And hopefully I've convinced you that live cell imaging is both fun and sometimes informative.

We've learned quite a bit about how viruses work and how cells work.

And some of these discoveries have been relevant to thinking about new therapeutic strategies.

And, again, I think in the future, combining live cell imaging and different fluorescent imaging based platforms is going to be tremendously useful with new statistics and new computational models for setting up these model systems, for understanding how viruses work, the next generation of drug screenings and even new clinical diagnostic tools.

And finally, the most important part is the people who did the work.

So, in my lab, I showed work from Jordan and Ginger, who've done the-- Jordan's done a lot setting up the visual system.

Ginger is our image analysis guru.

Jay Gardner is working on the cell-cell transmission system.

And I'm grateful to everybody else in the lab.

We have fantastic collaborators on campus doing a lot of different viruses and imaging projects.

I especially emphasized Paul Ahlquist and the Morgridge Institute for their investment in virology and helping young faculty on campus.

These guys, Walther and Mike, were my mentors who provided a lot of the ideas.

And then the people that make the research go.

So we have funding from the NIH, the Shaw Scientist Program from the Greater Milwaukee Foundation the Wisconsin Partnership Program, and we just got money from WARF, UW2020, to buy a new microscope.

So, we're incredibly grateful for all those contributions.

And I'll put this slide back up on there.

Make sure you "like" McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research on Facebook.

[laughter] And I'm very happy to take any questions.

[applause]

Support for PBS provided by:

University Place is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

University Place is made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.