Create a Family Legacy: Backyard Garden Seed Saving

Special | 45m 39sVideo has Closed Captions

Michael Washburn shares stories about heirloom seeds and tips for saving your own seeds.

Michael Washburn, Preservation Director at Seed Savers Exchange, presents tips, techniques, and stories about heirloom seeds, and how to create a living treasure for your family by gardening and saving seeds from year to year.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

University Place is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

University Place is made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Create a Family Legacy: Backyard Garden Seed Saving

Special | 45m 39sVideo has Closed Captions

Michael Washburn, Preservation Director at Seed Savers Exchange, presents tips, techniques, and stories about heirloom seeds, and how to create a living treasure for your family by gardening and saving seeds from year to year.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch University Place

University Place is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Experts share horticultural research and gardening tips for Midwest growers. Discover techniques on topics from vegetables and native plants to beekeeping and sustainable landscaping. These talks help gardeners of all levels create beautiful, productive and ecologically sound spaces at home and in their communities.

Video has Closed Captions

Cora Borgens explains why and how to prune woody plants for optimal plant health. (50m 56s)

Video has Closed Captions

Patrick Smith uses principles of improv comedy to create a sustainable garden. (49m 23s)

Indoor Gardening for Food and Fun

Video has Closed Captions

Victor Zaderej offers practical advice on how to easily grow produce indoors. (49m 6s)

Wonderful Wool for Your Plants and Your Planet

Video has Closed Captions

Elaine Becker and Karen Mayhew describe how wool is a healthy soil alternative to peat. (48m 2s)

New and Unique Plant Varieties

Video has Closed Captions

Horticulture specialist Allen Pyle showcases standout plants from 2024 trial gardens. (45m 16s)

Video has Closed Captions

Rachel Belida presents ideas for creating a seven-layer food forest in your yard. (45m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Becky Gutzman shows how to safely preserve your summer garden bounty for the rest of the year. (58m 35s)

Simple Steps to a Beautiful Rose Garden

Video has Closed Captions

Diane Sommers shares suggestions on growing roses for the home gardener. (47m 50s)

Video has Closed Captions

Alena Joling explains how to take care of your bladed garden tools. (50m 25s)

Preventing Bird-Window Collisions at Your Home

Video has Closed Captions

Brenna Marsicek explains why birds hit windows and how to make windows more bird-safe. (48m 47s)

Legacy Trees and the Prairie Savanna Project

Video has Closed Captions

Matt Noone and Cindy Becker introduce two Dane County area community science projects. (48m 14s)

Video has Closed Captions

Lisa Johnson offers best practices and tips for successful container gardening. (50m 16s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Welcome everyone.

Thanks for attending today.

So glad you came out today.

I'm Michael Washburn.

I'm the Preservation Director at Seed Savers Exchange.

It's nice to be back in Wisconsin.

I've spent most of my time in the South, in Texas and Kentucky and Tennessee.

Now, I did spend my high school days just north up in Neenah, Wisconsin, but that's been many moons ago.

So I currently live in Decorah, Iowa.

That's where Seeds Savers Exchange is located, but it's nice to be here with you.

So thanks for having me.

So I've titled this "Creating a Family Legacy: Backyard Garden Seed Saving."

So here are the objectives of the talk.

So we're gonna reacquaint ourselves with what an heirloom seed really is.

I'm gonna provide three extraordinary examples of what heirloom seed stories are.

I'm gonna cover some basic seed saving techniques of our most popular crop types, and then I'm gonna explain how seeds are truly preserved in your backyard.

And then I'm gonna provide some ways that folks can get involved.

So what is an heirloom seed?

Well, co-founder Kent Whealy first heard the term "heirloom" from the infamous bean collector John Withee.

John and Kent were at a conference and John referred to an old seed as an heirloom seed, and that really struck Kent.

And so Kent asked John, he's like, "Well, hey, can I use that term heirloom?"

And he said, "Well, heck yeah, 'cause I stole it from somebody else."

[audience laughs] So what makes it an heirloom?

Heirloom seeds are a historical record of continuous human selection of desired traits in order to nourish and feed one another.

Here's some aspects of what makes it an heirloom.

The farming culture, what techniques people used, harvesting traditions, how to harvest it, when to harvest it, maybe some ceremonies around that harvest, dishes the family made.

What common dishes were cooked with a certain variety?

Maybe special events or holidays that were centered a certain crop.

And of course, the family stories that went along with it.

So I'm gonna tell you of three wonderful examples of heirloom seed stories that go along with those seeds.

So we'll talk about John Withee, the man I just spoke of.

So he and his family had an heirloom practice that was handed down over the generations in how they cooked their beans.

They cooked them in what they called the bean hole.

And this is how they cooked their Saturday night supper.

So John was in charge of this.

They had a hole dug in the front yard.

It was about the depth of two traditional Dutch ovens.

It was lined in bricks, wide enough to lower a Dutch oven down in, and it was John's duty to get some hot coals going and cover the Dutch oven, then cover that up with dirt.

And he did that on Friday afternoon.

And those cooked until that Saturday night supper.

So as a young fella, John was a market gardener, and he did that to help out his family financially.

And this was the first time that John had grown beans on a large scale.

Now, John preferred to grow pretty beans.

He said that's what gave him his success at the farmer's market, just how beautiful all the beans were that he sold.

John was also quite the adventurer.

He had a bunch of explorer buddies that introduced him to all kinds of places to explore.

He took a couple trips to the Arctic, but he really enjoyed the Rocky Mountains.

But every year, he made it back to Maine in time to put out that garden.

So later on, John found him a good job as a medical photographer in Boston.

So he moved to the suburbs of Boston.

Now he said that move caused him what he called some bean trauma, [audience laughs] 'cause he was moving around, apartment to apartment, no yard to garden in, no place to put that bean hole.

So finally, John and his family left Boston when they purchased some land in Lynnfield, Massachusetts.

And this is when he set out to reestablish that family tradition of cooking the beans down in the bean hole.

Now, he could easily remember how to recreate the bean hole, but what he couldn't find is those old family beans.

And that family bean is what we know as the Jacob's Cattle Bean.

So amongst the heirloom bean collectors, that's kind of a common bean now.

A beautiful bean, has wonderful mottling on it.

And so he realized the only way he was gonna be able to recreate that Saturday night bean supper is if he could find that family bean.

So John set on a hunt to find it.

And this journey led him to other families that also had their family bean.

They also had their own stories.

But too often, that story ended in, "Well, we lost the family bean."

So that prompted John Withee to start collecting these beans and collecting those stories, and growing them out and preserving the beans along with those stories.

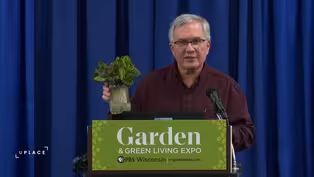

That's John and his bean collection there.

So John spent nearly two decades stewarding one of the largest bean collections in the United States.

In the process, he organized like-minded seed savers and united a community of passionate gardeners under his nonprofit, The Wanigan Associates.

So as John got up in his age, he decided to donate his entire collection to Seed Savers Exchange in 1983.

And for the last 40 years, with the help of this exchange community and Seeds Savers Exchange, they've all been growing out John's collection and sharing them with others.

Now, if you go in our database at Seeds Savers Exchange, which houses all the data in the seed bank, if you go in bean number one, that's John's.

Bean number 1 through 1,185, that's how many beans John collected.

That's my first story.

My second story is about Regina Santore and her Rizzi Softball Plum Tomato.

Pretty large plum tomato there, isn't it?

So if you read the 2022 Exchange Yearbook, you would see Regina say, "I need your help to keep these seeds going."

Regina Santore is from Knoxville, Tennessee.

That's where I'm from.

And she stewarded this heirloom seed there that's been in her family for over 100 years.

Now, the seeds came to the U.S. with her great-grandfather and grandfather to upstate New York from Barletta, Italy at the turn of the century in 1900.

As soon as Regina's grandfather Vito and his father, her great-grandfather, had space of their own, Vito wrote his sister in Italy, and he wrote in Italian, but that translates to, "Send me those tomato seeds."

So in order to not get busted by the mail system, his sister put that in the glue of the envelope and sent those to Vito.

And ever since he got those, Vito's entire backyard was dedicated to those tomatoes.

And not only did Vito raise these every single year, he carefully selected the best seedlings to put in the garden.

And he watered and babied those plants with his water-manure mixture.

I've got an old buddy down in Knoxville, old timer, babies his plants just the same way.

Hand-waters every single one of 'em.

So when Vito passed, Regina's uncle, Lou Rizzi, took over the stewardship.

Lou is on the left there.

And of Lou's four brothers and four sisters, Lou was the only one that continued the stewardship of the Rizzi tomato that was eventually handed down to Regina in 2010.

So Lou had said he had found these in a vial of seeds in the '40s and said that they germinated no problem.

And so when Lou can no longer continue to raise them due to health reasons, Regina took over in 2010, and Uncle Lou passed in 2019.

That's Regina Santore.

Regina wrote in the yearbook, as people describe a little bit about themselves, she said, "She's in love with vegetable gardening "and sustenance techniques in general.

I've even made my own cheese."

She's also a classically-trained soprano and an avid ocean fisherman.

Folks generally tell a little bit about themselves so y'all can get acquainted with them.

So these are huge compared to normal plum tomatoes.

Each weighing about 10 ounces.

And she says they can be a good slicer, but they really shine in a tomato sauce.

She says there was always a distinct smell that came from her grandmother's basement kitchen and it's etched in her brain, the smell of those tomatoes being turned into tomato sauce.

And it's kind of funny, she and her cousin always wondered why her grandmother never offered her any when she was down there, until later they realized she was just down there canning 'em and not just down there eatin' 'em.

[audience laughs] [clears throat] And so Regina says, "I save my tomatoes from only the best tasting fruit."

And when saving them, she waits 'til that nice white mold is over top from the dish of seeds and water.

She keeps 'em in there 'til they stink, she says, and then she dries them out on a towel.

And that's the way her uncle taught her.

And she says it works perfectly.

And that her germination rate of her seeds is very high.

Now Regina experienced some difficulties, unlike what they'd experienced up in New York, due to the hot growing conditions in Tennessee.

So she counteracted that by planting her tomatoes really deep in the ground.

She put irrigation on 'em with plenty of ground cover.

And so here's a new practice needed to adapt to a different climate.

She continued to write; she said, "I've done my best to raise at least a few each year, but I need your help."

And she'll give you the seeds for free as long as you promise to list them in the exchange.

So since then I've asked my old buddy, John Coykendall, down in Knoxville, Tennessee, who's a longtime Seeds Savers Exchange member, to help her save those seeds, since he's in her neck of the woods.

And so we also have those seeds at Seeds Savers Exchange, but they're a lot better living in the backyard in John's garden in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Also got a goat farmer buddy down there that says he's gonna help her out.

So we'll go to my last story.

It's about the Fortna White Pumpkin.

So Sue Ellen Fortna Majer, she's the daughter of Wayne Fortna.

So Sue's dad, Wayne, grew up raising these pumpkins his whole life, and he saved the seed year after year.

And he got them from his family that came from around the Franklin County area in Pennsylvania.

And they were always just known as the white pumpkin until the seed got spread around in Sue's mom's family, and they renamed it the Fortna White Pumpkin.

So Wayne's parents were farmers and teachers, and Wayne was also a teacher until he got called to duty in World War II.

And upon his return, he realized that he had what we now call PTSD.

And so he wasn't able to go back to teaching.

And so Wayne took up gardening.

And Sue says that it got him back into the soil and back into nature, as she recalls.

She said gardening saved him.

She says it's a great pie pumpkin and that they're easy to grow.

And Wayne was very particular in where they grew in the garden.

He'd grow cucumbers on one side of the garden and the pumpkins on the other side of the garden, right up next to the corn.

And he had trained those vines to go into the corn.

That might sound like a familiar practice, maybe like three sisters, right?

He trained the vines to go into the corn.

Acts as a weed suppressant, keeps the ground moist, and allows all the water that the corn needs.

[clears throat] So Sue's father Wayne passed in 1990, but she continued to grow the pumpkin out year after year because it was the tradition that they used that pumpkin for the Thanksgiving pumpkin pie.

And his passing prompted her to share the seeds with the Landis Valley Farm Museum in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

And her hopes was that they would continue to grow the pumpkin out and be an additional steward of the seeds.

Now, her action to share the seeds with the farm museum played a key role in the continuation of this heirloom.

Because after 25 years after Sue inherited those seeds, she actually lost them.

So she wrote the Landis Valley Farm Museum and admitted that she wasn't quite the farmer that her father Wayne was, and that she had accidentally let the seeds mold.

Luckily, the Landis Valley Farm Museum had been growing them out and was able to reunite Sue with her heirloom pumpkin.

And you can actually go on the Landis Valley Farm Museum site today and order the Fortna White Pumpkin from them.

I suggest you do.

So those are some great examples of all the various forms of culture that an heirloom seed can encompass.

So now I'm gonna just tell you a little bit about some aspects of saving your own seed.

So here's how to save some seed on some of our most popular crop types.

So in John Withee's honor, we'll start with the common bean.

Now this is a great one to start saving seed on.

It's an easy one for beginners.

When you're looking at isolation distance, it's very short.

Only need about 10 to 20 feet.

It's a self-pollinating type, that's why the isolation distance is very short.

It's also easy to tell when the seeds are mature.

It's when they're dry down on the vine and those pods are nice and tan, well, now you know it's ready.

So for variety maintenance, for the population, for a backyard gardener, five to ten plants is great.

And so if you look at these, the one on the left, of course that's not ready.

The one on the right there, so we're getting close.

I bet you that pod's a little squishy yet.

But then that's what we're looking for right there.

So when they're nice and tan and papery, you can go ahead and hand-shell those out.

It's a good thing to do on the front porch with friends and family.

If you've got a good wood-burning stove, it's nice to sit around that and have a chat, everybody sit around and shell beans.

It's a good old pastime.

Now once you shell those out, get you a bowl in the kitchen in indirect sunlight, put your beans in there.

Couple times a day, put your hands through 'em, let 'em air out a little bit.

It's kind of therapeutic.

After a month, they'll be good and dry and you can go ahead and put 'em in a Ziploc bag and put 'em in the freezer and then they'll store indefinitely.

Tomatoes.

The most popular backyard garden crop type there is.

We've got 7,000, 8,000 varieties in the seed bank at Seed Savers Exchange.

Again, another easy one, isolation distance is very short.

10 to 50 feet will do it.

Again, it's a self-pollinating type, so it's a perfect flower.

It's generally pollinated by the time the flower actually opens.

Some of 'em will have the stigma that sticks out a little bit, so that's where some cross-pollinating can happen.

But you're pretty good with 10 to 50 feet on isolation for tomatoes.

Again, market maturity is when the seeds are ready.

So when that tomato is ready to eat, well, the seeds are ready.

Now, my old buddy Johnny lets 'em hang on just a little bit longer just to make sure they're perfect.

But when they're ready to eat, they're ready.

And you can do like Regina does and try 'em out and then only save seed on the best-tasting ones.

Again, population size, five to ten plants for a backyard garden is great.

If we do it up for strict genetic preservation, we're gonna grow about 20 plants up at Seed Savers.

So the processing for seeds is a little bit more than that.

So you gotta take that tomato, cut it open, squeeze it out into a jar or another container.

But we need to do some fermenting, 'cause that gelatinous sac around the seed, that keeps it from germinating inside the tomato.

So we gotta break that down through a fermentation process.

So you let it sit for two to three days.

In that bottom picture there is little bit of that white fuzz that Regina talks about.

And so my old buddy says that when they start to look bad and smell even worse, well, you know you're on the right track.

[audience laughs] So after that, you go ahead and put 'em out in your strainer, spray 'em out real good, get all that gelatinous material out.

It's gonna be tough to get 'em that clean, so don't worry about it; get 'em as clean as you can.

And then you wanna spread 'em out on a sheet tray or a screen or a baker's mat.

Don't put 'em on a paper towel; they will stick to it.

Now, we do have this one lady that sends them in to Seed Savers Exchange and she cuts the little paper towel out with the tomato seed on it and that's how she plants it.

Works out, right?

[audience chuckles] Now, we wet it and pull the seed back off and dry it to get it back into the seed bank, but try to just put it on something not paper.

And again, get that in your kitchen bowl.

Once they kind of dry out, break 'em up, they'll stick together, once or twice a day, indirect sunlight, put your hands through 'em, give 'em some air, and then into the freezer.

They'll stay there indefinitely.

Let's talk about squash.

This is one of my favorite ones to save.

Now if you notice the isolation distance, pretty far, 800 feet to half a mile.

Insect-pollinated, so they like to fly pretty far.

So that's why you can get crossing on that.

But don't worry, I'll give you four types so we can put in the garden and not worry about 'em crossing.

So market maturity on your winter squash there, when they're ready to harvest and bring in, that's when your seeds are gonna be ready.

Yet you still do wanna let it sit around for at least 20 days once you harvest it.

You know, three weeks to a month is great.

The longer you let the winter squash sit, the sweeter it'll get, 'cause your sugars are gonna concentrate.

So let it sit around as long as you can.

Now for your summer types, it's a little bit different 'cause we eat our summer types at an immature stage when they're nice and tender.

So you know those zucchini that are hidden from you and get away from you and turn into baseball bats?

That's the direction we need to go to start saving seeds on a summer squash.

But I'll talk about that a little bit more in another slide.

So the argyrosperma, that's the class of the Fortna White Pumpkin.

So there's one we can save.

It's also your Cushaws and your other silver-seeded gourds.

So you could save, you could grow the Fortna White Pumpkin, and then you could grow it along with maybe a Blue Hubbard, and that's in your maxima class.

So you can grow both of those out together without those crossing.

So now we're up to two winter squashes in the garden.

Also include your banana squash and your Kuri squash.

So now we've got two.

And you can add a butternut squash to that collection.

So now we're up to three.

In the lower picture there is the Musquee de Provence, which is a wonderful French pumpkin.

Also your Kentucky Field pumpkins.

The moschata class is a easy one to tell because it's your tan skin types.

So your Kentucky Field pumpkins and all your butternuts, all your tan skins, those will be your moschata class.

So now we're up to three winter squash that we can grow in the garden at the same time without anything crossing.

And then what fits perfectly right in there is our summer squash, in the pepo class.

So now we've got three winter squash and a summer squash.

And that'll be your zucchini, your crooknecks, your patty pans.

You do gotta be careful; it's your acorns and some decorative gourds, your jack-o'-lanterns types, can also be in the pepo class.

So you have to make sure you get those right.

But don't worry, I'll give you a good guide to straighten all that out.

So again, back to how to save the summer squash seed.

Well, we always have too much squash or too much zucchini, so go ahead and cut and eat and eat 'til you're plum full of it.

And towards the end of the season, let those big baseball bats growing out, let 'em turn color, leave a couple on each plant, and cut 'em off before they rot.

Let 'em sit around as long as you can before they rot.

Cut the seeds out and then you can pretty much process 'em all the same way.

So you'll cut 'em in half, you'll scoop the seeds out.

A quarter-inch mesh is a good strainer size for the squash seed.

Get you a sprayer, spray it all out.

You can even put 'em in a bucket and soak 'em for a couple hours with water and that'll help loosen everything up, get all the pulps and strings off of that.

And then again, screens are really good with the squash seed, lay 'em out on the screen.

Baking sheet will work all the same.

As they start to dry, kind of unstick 'em, get 'em back into a kitchen bowl, get your hands working 'em a day or two, a couple times a day for about a month.

And then again, Ziploc bag into the freezer and they'll store indefinitely.

And peppers.

This is where the tough decisions get made.

Again, a large isolation distance on that.

So we're saying 300 to 1,600 feet.

I generally feel pretty good about 750 feet on that.

But unless you've got a really big yard or you got a buddy down the road, one can do a hot, one can do a sweet, you're gonna have to make a difficult decision.

Because even though they are self-pollinated, there's a good chance you'll get insect crossing on those.

Seed maturity's really easy on this one.

Whatever color the pepper's supposed to end up at, if it's red or orange, that's when your seed's gonna be ready.

Seed comes out clean, as we all know, when you open up a pepper.

So it's a pretty easy one.

You can just pull it right out there, get it on a sheet, start drying that, go ahead and eat it.

Population size, pretty easy again, five to ten plants on that for your backyard, and you feel good about your genetic diversity and maintenance on that.

The one there on the right, that's the fish pepper, it's a good hot pepper, it's absolutely one of my favorites.

And then the other one is the Wisconsin Lake Sweet Pepper.

Might do well up here for some reason.

Lettuce, everybody grows lettuce, another super easy one.

Isolation distance very short on that, 10 to 20 feet.

So you could grow a couple varieties of that, depending on how big your garden is.

Self-pollinating.

So it's pollinated by the time the flower opens.

So maturity on that, I'll go to the next slide so you can take a look at that.

We've all seen that, got your spring lettuce, gets all hot, starts to shoot up and bolt.

It's going to flower at that point, and it'll start to set seed.

And then the picture with the bag over it, that's a good way to save seed.

And they call it the pappuses.

So as soon as that seed's done, it's gonna start to open almost like a dandelion, got those frillies in there.

And so right before that pops open, that's when your seed's ready.

I mean, if it opens, it might float away on you, but when the plant's got about a third to a half of those, you can go ahead and take a bag or something and start shaking 'em in there.

And that's a good way to get your lettuce seed.

Now, we do it with the bags, then we're able to just kind of keep knocking 'em out in the bag and then all the seeds drop in there, and it's a good way to get all the seeds off of a harvest.

But yeah, lettuce is a pretty easy one to save on 'cause it is an annual seed crop.

So now your Brassica oleracea, that's your broccoli, your cabbages, your cauliflowers, your kales, and my favorite, the collard.

Again, you can see the isolation distance on there.

Another tough decision.

So 800 feet to a half mile on that one, 'cause it's insect-pollinated; as we stated, they like to roam.

A little bit more complicated 'cause it's a biennial seed-producing crop.

So it's gonna produce seed on your second season.

So you put your fall crop in of your broccoli or your kale or your collard, and you gotta overwinter that.

And down south, it's pretty easy.

We can just leave it in the ground.

Up north, a little bit different, unless you've got a hoop house and some row cover, maybe double row cover inside of there, you can keep it in the ground.

Otherwise you're gonna have to dig it up in late fall and get it into a root cellar or garage.

As long as you've got it between 34 and 39 degrees, and putting some sand and keeping those roots kind of moist.

Don't wanna let 'em rot.

And then you can reset it out in spring, it'll re-root and go ahead and go to flower and go to seed.

Population size on that one, a little bit higher, 20 on that, five plants will still do it.

I jazzed this one up to look pretty.

[audience chuckles] That's Alabama blue collard, absolutely gorgeous.

And so those are the bolts I got sitting in the leaves there.

And at the very bottom, the middle one, you can see that's that little bolt coming up, looks like a tiny little broccoli.

It's absolutely delicious; it comes on in spring.

You can eat it just like broccoli.

And then those are the flowers up at the top.

And soon as they set flower and go on, they'll go on and set seed and they'll make a little tiny pod, about three to four inches.

And its maturity kind of looks like the bean.

It's that paper, kind of tan pod, and that's what'll have your seed in it.

So you can take a bag over next to those and just kind of dump it in there.

Now, they will shatter on you and start to spread seed on their own.

So just bring a bag over with you and start knocking all your seed into there in spring when you get to that light, papery part.

And you'll have plenty of seed.

So you can grow all those varieties in the fall, and then just select what do I want to go to seed, and set that one out in spring.

So if you want to save seed on the collard, just harvest everything else, go ahead and set that collard out in the spring, and then save seed on that.

This is another great one for all you garden school teachers, if we have any in here.

This is one that works good for the school year because the kids are in school in fall and you can put that out in the fall, overwinter it with them.

And then in the spring, y'all can harvest seeds together.

So it's a great one for the school.

But you don't have to sit and memorize all this.

There's a great guide out there called "The Seed Garden."

This happens to be my favorite one; I still refer to it.

It has all your crop types in it.

It's very easily explained in there.

Sends you through all the steps.

For your squashes, it'll make that all nice and neat for you, so you don't have to remember which one.

Was that the Fortna, the Blue Hubbard, or maxima, or what was that?

This is a excellent guide.

So encourage you to get that or find you another seed saving guide.

There's quite a few out there that'll kind of guide you along.

And it'll also show you that this is a really easy process of saving seeds; it's not difficult.

So I wanted to show you this.

This is the inside of the seed bank.

And it was really the gardening community that dictated how the seed bank grew.

And it was developed out of the seeds people cherished and wanted to save or maybe had nobody else to steward it.

And so the seed bank at Seed Savers Exchange was created by the donors.

And so this is a good takeaway of having somebody else steward the seed, kind of like Sue did, in asking the Landis Valley Farm Museum to help her steward.

Now, it's nice to have 'em in the Seed Savers seed bank, but true preservation happens in your backyard.

And this is where I'd like to make my most important point about this talk.

Because we're simply a holding place that stores the seed in hopes that somebody else will request them and start growing them in their backyard.

So we identify seeds that have a low population or might have a low germination rate.

And so we'll grow them out to get their quantities up so we can share them with others, or we'll increase their germination rate so you find success when you do request them.

So if they sit in a seed bank, they're considered functionally extinct.

They're alive, but they're not doing anything.

They're not out in the world being adapted by you.

So it's our job to keep them alive and then figure out how to get 'em in your backyard.

And that's where the growing community comes into play.

So we're hoping that you'll write us or email us or better yet, get on the Exchange and request some seeds and start learning the farming culture behind some of these seeds.

Just like Sue's father, Wayne, grew the Fortna White Pumpkin on the edge of the cornfield, serving its dual purpose there.

And we need you to start selecting for desirable traits, just how Regina saved seed on the best-tasting tomatoes.

She's therefore selecting for generations of flavor.

Put 'em in the dishes that your family makes, just like John Withee did, in his Saturday night bean supper.

Incorporate 'em into your special holidays or events, kinda like the Fortna White Pumpkin and Sue did for that Thanksgiving pie.

And then start creating family stories.

It's many times the stories are just as important as the seeds, 'cause they reflect the history of a family or a community.

They need to be living in your backyard.

They need to be selected for you by the traits that do well in your zone, in your climate, and taste good on your plate in your family dishes.

And that's when people really find value in the seed.

It's when they come with rich stories that reflect the culture and the families that stewarded them, and they make it attractive to others and make people want to grow them.

Talk about some ways to get involved.

I've talked a lot about this Exchange Yearbook.

It's a community of gardeners and seed stewards that are sharing and swapping heritage seeds that you just might not find anywhere else.

Now, you can go in this book and you can search by crop type.

If you like corn or you like beans, you can go in there and find all the varieties of corn or all the varieties of beans.

You can also go in there and search by state and find somebody in your state that's sharing their seeds on the exchange.

Chances are they're gonna do good for you.

So find somebody in Wisconsin, see what they're growing and sharing.

Like I said, there's a good chance you'll find success.

Now, the exchange works to keep biodiversity strong and garden traditions thriving.

And in this book, there's over 15,000 unique varieties in it.

I actually got my first request just a couple days ago.

The Exchange, the new volume just came out a couple weeks ago, and somebody from Michigan requested this old, pre-Civil War Tennessee okra.

So I hope they get her started early.

[all chuckling] And this is your doorway into the vault at Seeds Savers Exchange.

And I don't really like the term vault because it sounds inaccessible, and it's absolutely not inaccessible.

So we want people to get these seeds and we want 'em to grow 'em.

And again, biodiversity must be stewarded in the backyards of gardeners.

So another fun project we have is the Collection Documentation Project.

So that's where we have a variety that doesn't have a description to it.

So here's an example.

So we got Lloyd Dudley here, and he donated this seed in the early '80s, but we have no other information on it.

So you go in there, you find one that doesn't have a description, you request the seeds, we send them to you for free, and then you grow 'em out.

You just make observations of the plant, as much detail as possible.

General growing habits work, physical characteristics of how it grows, the fruit.

Does it grow uniformly or is there variation?

How does it produce?

And what's it taste like?

Take some pictures, and then at the end of the season, compile all those notes into a paragraph, send it to us, and then the next year's Exchange will come out with your description.

And then people are more inclined to request that variety, if it has a description.

So that's a good one for people to get involved with.

We also have the ADAPT program.

It's a community science program.

Currently, we have 710 participants.

Closing on that happens next week.

As far as I know, it's the largest community science project in the country.

So we'll offer you six to ten different crop types each year.

And these are all varieties that come outta the collection.

And so for each crop type, we'll choose eight or so varieties.

And we'll also use a control from our catalog.

So we'll choose a variety, let's say we're doing cabbage, we'll choose a variety from the catalog to be the control for that.

And so then we'll randomly pick three varieties of that crop type and we'll send 'em out to you.

So if you choose the beet trial, we'll randomly select three of those beets and send them to you.

And then each participant can do up to three trials.

So you can get involved in our sunflower trial, our collard trial, and then maybe the beet trial.

And so the first week of March, we'll send you out with your seed packet and your little growing kit.

You'll have plant labels and a data sheet and instructions on how to submit your data.

And then we're asking you to just evaluate on a handful of key characteristics.

So we're looking for yield and flavor, earliness, appearance, disease resistance, and, of course, flavor, as I mentioned.

And then we're gonna ask you to enter the data on this nice web platform called SeedLinked, and it's a really nice platform.

You can look at what other people are growing, what other people are saying about the crop type that you're growing.

It's a pretty neat platform.

And so this is a great way to determine what might be a good candidate for the catalog.

So if everybody's saying, "Hey, this one's just great, and it grows well here," well, that's a good candidate for the catalog.

So that helps us in the process of selecting, and that's the way the community gets involved with selecting what might be in the catalog.

We've got the RENEW program.

This is another community science program.

And so we ask more experienced growers to get involved with this, and they're helping with the seed regeneration of things in the seed bank that we don't have large quantities of, or the germination rate is low.

So if we don't have enough to share, we can't list it in the exchange.

And so this is the way the community helps us get those quantities back up and gets them in good shape so we can list 'em to the exchange and make 'em available to the public.

We're pretty strict on the parameters there.

Looking for a certain population size, isolation distances must be pretty strict.

And then the harvest quantity so we can get that quantity up again, like I said, so we can share it with the public.

So the seeds are sent back to us.

The next season, we'll do what we call a lot check, and this is just where we're making sure that purity was maintained.

And as soon as we see that purity was maintained, the following season, we can then offer it on the exchange, and it's back out in the public hands, exactly where we want it.

Now this is a super fun project that I'm involved with.

It's the Heirloom Collard Project.

So this is a collaborative effort to restore collard diversity, and it's working to preserve the culinary significance of it in American food culture.

And so it's a great group of folks involved in this.

So we've got Ira Wallace from Southern Exposure Seed Exchange involved and Chris Smith from the Utopian Seed Project, and Bonnetta Adeeb from Ujamaa Cooperative Farming Alliance, and Phil Kauth from REAP right here in Madison's involved.

Unfortunately, I can't list everybody.

It's a wonderful group; go to the website, check it out, super fun.

So in the late '80s and '90s, a couple fellas drove around for seven or eight years in the South, looking for shiny collard patches in people's backyard.

Go knock on their door, ask 'em about those collards, got some seeds from 'em, collected around 72 varieties, donated it to the USDA.

And then a few years ago, Ira Wallace and Seed Savers Exchange requested those from the USDA and we started increasing those quantities.

And then now, we just ask people to grow the collards out, tell us what you think.

We're asking people to help increase those seed quantities so we can continue to share 'em with people.

And again, this is a great one for schools.

We just got the Edible Schoolyard involved and they're super pumped, and they're gonna help grow 'em out and help reproduce the seed on that so we can continue to share with others.

Great project, check that one out.

And the last one I'm gonna talk about is the Community Seed Network.

And this just really connects and supports a community of seed initiatives, and it provides resources and information and platform for sharing and networking.

So it's the joint initiative by Seed Savers Exchange and Seed Change, and it just facilitates seed saving and sharing.

Places to connect, there's a great map, you can go in there of the world, and it'll show you all the seed initiatives located all around the entire world.

There's a place to share, there's a good Facebook group in there.

We also offer a link to the exchange there.

And then a place to learn, a lot of good seed saving resources on this site, as well as on Seed Savers Exchange site.

Some other good organizational resources as well.

And again, we're just one of the many organizations around the country involved in efforts to engage and educate others on how they can help preserve biodiversity of our food ways and the cultures that are intertwined with it.

This is my son, Fields.

[audience laughs] He's got him a nice harvest of cucumbers there.

I believe that's the Middle East Peace Cucumber.

It's offered by True Love Seeds.

I'm a big fan of True Love Seeds.

They have some great varieties on there.

But I just want to thank everybody so much for their time and attention, and I hope those that are involved continue to keep up the good work, continue to mentor and share your knowledge with others.

And for those that haven't begun, find you a mentor and just start seed saving 'cause like they say, there's no time like the present.

Thank you so much.

[audience applauds]

Support for PBS provided by:

University Place is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

University Place is made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.